Andy Warhol built his empire on repetition, from rows of Marilyns to stacks of soup cans. But behind the final, iconic images lies a lesser known layer of experimentation: the trial proof. These are the moments where Warhol broke his own rules, testing colors, compositions, and moods in ways that reveal the inner workings of his creative mind.

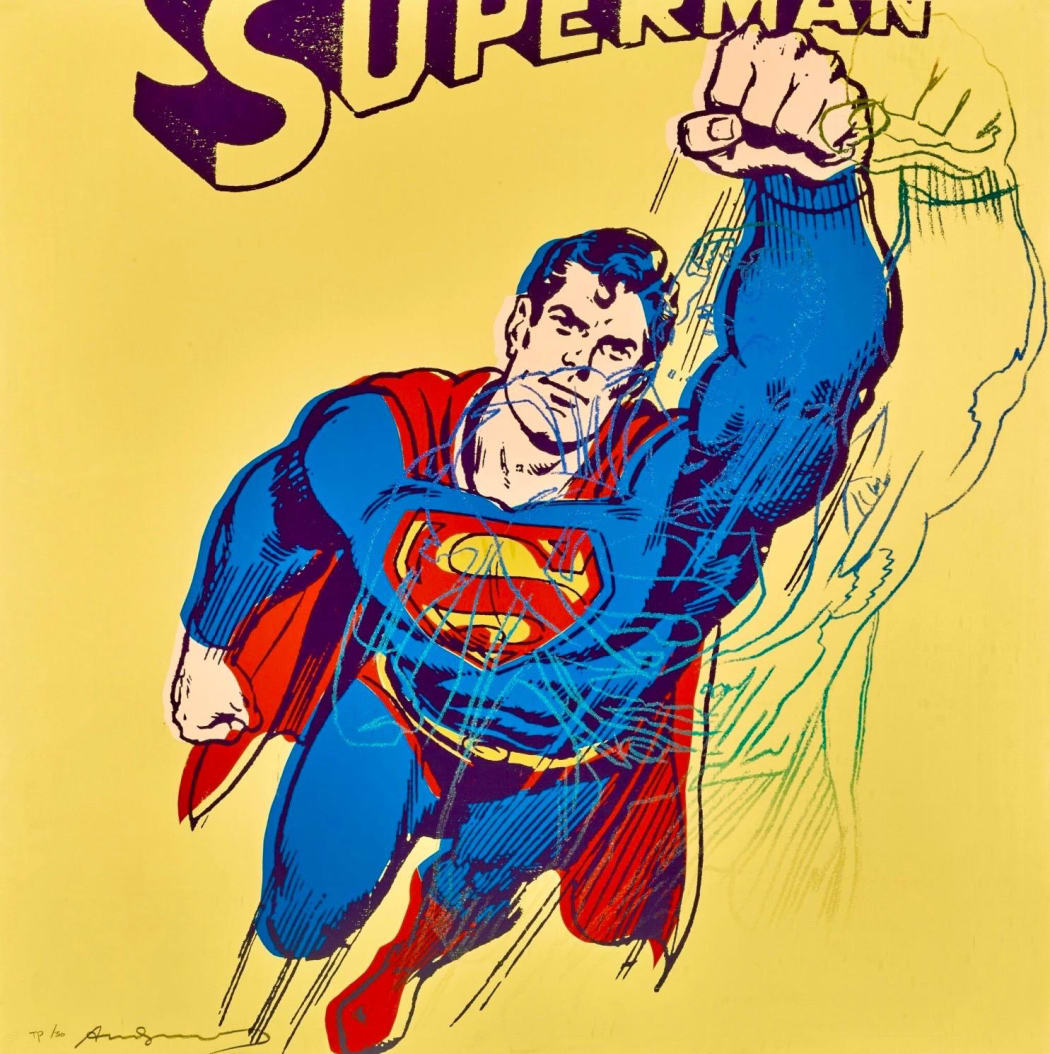

A trial proof is traditionally a test print, a means for artists to adjust ink, paper, and alignment before printing the final edition. For Warhol, though, it became something more. Rather than simply being a mechanical process, it became his playground of improvisation. In them, he explored color in ways that could dramatically shift a viewer’s perception. The same image could feel bold and brash in one proof, then soft and melancholic in another. A pale blue Marilyn whispers. A fiery red Mao shouts. Each trial proof becomes its own personality, and its own unique variation.

This process was a collaboration of sorts, between Warhol, his studio assistants, and the screen itself. Multiple proofs were often produced in rapid succession, with color swaps and slight adjustments piling up in layers. Warhol would study them, react to them, and ultimately decide which version carried the visual and emotional punch he wanted for the final edition. The trial proofs that remained, often unsigned or marked uniquely, became rare glimpses into the deliberation behind the polish.

What makes these pieces so compelling today is their blend of familiarity and surprise. We recognize the faces, the forms, the Warhol “look”, but the trial proofs break the uniformity we associate with his work. They introduce the unexpected. A splash of neon here, an off-kilter registration there. These imperfections and detours remind us that behind the myth of Warhol as a mechanical producer was an artist deeply engaged with intuition, editing, and nuance.

In a body of work so often defined by sameness, the trial proofs stand out for their singularity. They are exceptions that expose the process, the experimentation, and the hand of the artist himself. They are, in many ways, the most honest Warhols of all, not yet finalized, not mass produced, but captured mid-thought.

And that’s perhaps the greatest irony of Warhol’s legacy: in celebrating the repeated image, he left behind some of his most fascinating works in the ones that didn’t quite repeat.